It’s not just “laymen” that make this mistake. There have been plenty of academics who have challenged the idea that science makes genuine progress. Thomas Kuhn, whose writing appears in my undergraduate philosophy of science textbook, characterized science in a way that makes it more a matter of social consensus than objective validity. According to Kuhn, science consists of a series of problem-solving paradigms. In Kuhn’s model, a scientific revolution occurs when scientists decide to switch from one paradigm to another. In these situations, both paradigms are capable of solving problems. The switch comes because scientists decide that the problems solved by the new paradigm are more important than those solved by the old. This could mean that they have more social implications, or that more funding-providers are interested in them, or that the scientists just enjoy them more. Regardless, in Kuhn’s model the transitions in science are arbitrary. There’s no objective reason that paradigm A is better than paradigm B. It’s the scientist’s subjective views or the subjective social pressure that determines which paradigm is accepted.

It is important to understand what this description, and other similar “science isn’t objective” descriptions entail. According to this model, the right social pressures would cause “the world is flat” to have more scientific validity than “the world is round.” We could easily revert back to Newtonian mechanics, and such a change would be no less natural than the change from Newtonian mechanics to where we stand now. In fact, in the minds of many, science is so arbitrary that it could very well tell us almost anything. Yesterday the earth was flat. Today it’s round. Tomorrow, it could be an octahedron for all we know. These people, who don’t understand why the flat-earth theory was abandoned, also don’t understand why it will never be picked up again, and why future theories will never have an octahedral earth.

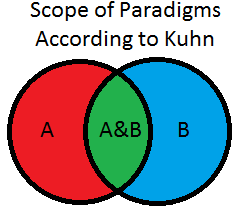

The problem with Kuhn’s model lies in a false implicit assumption. When Kuhn presents two potential paradigms, he assumes that the problems solved by the paradigms are somewhat disjoint. That is, in Kuhn’s model, there are some problems paradigm A solves that paradigm B does not, and there are some problems paradigm B solves that paradigm A does not. Kuhn does not explicitly state how much overlap there is between paradigms, but in order for his premises to support his conclusion (about the arbitrariness of scientific progress), one has to assume that there is at least some non-overlap. If we were to depict this in a Ven-diagram:

It is because of this non-overlap that one needs something other than the set of problems solved by each paradigm in order to choose between A and B. The choice will require some type of judgment call about which set of problems is more important, and this is where the subjectivity comes in. At least, according to Kuhn.

As anyone who’s actually studied the theory of relativity knows, this picture is woefully inaccurate. This is not at all how the transition from Newtonian mechanics to special relativity occurred. Nor does it accurately reflect the transition from classical mechanics to quantum mechanics, from flat earth to round earth, nor from stationary continents to tectonic plates. These paradigm shifts, and in fact nearly all such shifts in science, are more accurately described by this picture:

In real science, a new paradigm (B) that replaces the old paradigm (A) doesn’t just solve different problems. It solves more problems. Every single problem that Newtonian mechanics solves accurately, special relativity solves at least as accurately. Every single problem that classical mechanics solves accurately, quantum mechanics solves at least as accurately. Every single observation accurately predicted by a flat earth model is predicted at least as accurately by a round earth model. This is a phenomenon I call backwards compatibility. Any new scientific theory can’t just explain things the old theory fails to explain. A new theory also has to explain the success of its predecessor. It has to do everything the old theory does and then some.

At this point, there is no subjective judgment call. There is no problem prioritization that makes paradigm A better than paradigm B. It doesn’t matter which questions you want answers to, which experiments you care to run, or what research area society will fund. However you set up the subjective value judgments, paradigm B will always be better than paradigm A. Always.

This is why we say that relativity is better, objectively better, than Newtonian mechanics. This is why we say that the transition from Newtonian mechanics to relativity isn’t some arbitrary step in a random direction, but genuine progress. It is also how we know that we won’t go back. There is no re-prioritization that will suddenly make Newtonian mechanics look better than relativity. The two theories are not on equal footing. In terms of accuracy, Newtonian mechanics just isn’t as good.

But there’s even more we can gather from the realistic picture. Not only will we never revert to a flat earth theory, we will also never switch to an octahedral model. This is because the octahedral earth theory is not backwards compatible with the round earth theory. There are accurate predictions made by the round earth theory that are not made by the octahedral earth theory. Such a transition would at best look like something from Kuhn’s depiction, and that’s not what science does. While our model of the earth may change, it will change in a backwards compatible manner. Whatever new shape we use in our model will be sphere-like, so that all the success of the sphere shape is retained.

And this is the same throughout science. Whatever replaces general relativity, be it string theory or some other idea, is going to look like general relativity in “ordinary” circumstances, far away from black holes and over large distance scales. This is because general relativity is successful in these situations, so in order to make something purely better, we have to retain that success. Just like quantum mechanics is nearly indistinguishable from classical mechanics in macroscopic, many-particle interactions, and special relativity is nearly identical to Newtonian mechanics when velocities are much lower than the speed of light. And it is through this transitioning to new theories that have not just different successes but more, that we make genuine, objective progress towards an improved understanding of the universe.

I like the use of Backwards Compatibility, I think I will use this phrase. Kuhn's issue becomes apparent when he describes "abandoning" a previous paradigm in favour of a new one. This one word shows how his understanding is flawed. The correct word would be "absorb", or "dissolve". While it is true that there is no objective, or absolute frame of reference from which a given paradigm is to be judged, the scientific method itself, as you have eloquently commented, dictates that the new paradigm has to match ALL predictions at least as well as the preceding paradigm.

ReplyDeleteGood article.